Writing

Try to leave out the parts that people skip.

—Elmore Leonard

Baby boomer women are many and varied, and my stories reflect their experience:

Life in San Diego with a dog with attitude:

Sizzle and I chat about our adventures in Travels with Sizzle - Not a Sweet Dog Story on Substack.

If you start at the start, you’ll learn how Sizzle came to me as a criminal.

Read About Sizzle

Sizzle on alert

Single life in New York City (The New Yorker, Redbook)

Overnight motherhood (Sisters, A Novel)

Devastating illness, unthinkable decision-making and small, unexpected solaces (Riptides & Solaces Unforeseen, A Memoir)

Short personal essays about moving forward after loss (2becomes1: widowhood for the rest of us, my blog, and “10 Scary Things I Have Done Since My Husband Died” in Widows’ Words, an anthology)

Debby at the typewriter

Riptides & Solaces Unforeseen: A Memoir

Debby Mayer has written personal nonfiction that reads like a novel; she leaves readers with that elusive sense of catharsis only art can provide.

—George Held, Wilderness House Literary Review

The impact of terrible events is heightened by the writer’s understated, matter-of-fact prose, until the reader feels almost a participant in this tragic story. No one who reads it will ever forget this book.

—Molly Laird, RN, PhD, Emergency Room Psychiatric Nurse

I couldn’t put this book down!

—Penny Ribnik, October 2020

Ms. Mayer eloquently shares her painful experience in a manner both heartfelt and raw. Do we all not fear this? Losing a vibrant love, step by step, knowing there is no return to better days. But this is not just a story of sorrow. The author inspires with her resilience and dogged ability to do what must be done.

—R.L. Jackson, August 2020

+ From Riptides

From Chapter One / The Run

“They didn’t hurt,” Dan says about his legs. “They just didn’t move.”

It’s Monday, May 6, and Dan takes his usual run around the closed landfill two-tenths of a mile from our house. It’s circled by a dirt maintenance road that’s exactly a mile long—he measured it on his car’s odometer—and he customarily makes three or four circuits, running between a seven- and an eight-minute mile. He’s 55 years old, 6 feet tall, and weighs 170 pounds. He’s been running between four and six days a week since his 30th birthday. The previous winter was mild and dry; he didn’t have to cut back much.

On May 6, he has a terrible run. “3x,” he notes on his daily calendar; “40m [minutes], dead legs.” It’s bad enough so that he calls me at my office. “They didn’t hurt,” he says about his legs, “they just didn’t move.”

Dan, who works at home as a book editor, often calls me with one health complaint or another, none of which I can do anything about from my desk in the publications office of a college half an hour south of our house. His back hurts, or his stomach, or the inside of his knee. Few, if any, of these complaints drive him to a doctor; rather, he calls me at work, and I try to suggest what might be wrong.

This time I do sympathize. After living with him for 24 years, I still love him dearly, passionately. I want him to be healthy and happy, and running is important to him. He’s complained recently about slow runs—the previous week he had done only a nine-minute mile, which is more my speed—but what he describes today is new.

We go out that night to the movies, as we often do. We see Nine Queens, an Argentinean film about con men. Clever but unfair, I tell Dan afterward; the set-up takes place long before the opening scene. He dismisses this with a shrug, as he does a lot of what I say these days, and I’m a little bit hurt, but the film stays with me.

“Altered reality,” says my friend Margaret in a phone conversation the next day. “It’s disturbing.” . . .

Dan holds off running on Tuesday, and as we eat supper that night he says something about seeing a sports doctor. When my reaction apparently isn’t warm enough, he says, “Well, what do you think I should do?”

“—I think you should see a neurologist,” I say, surprising myself.

“A neurologist!” He packs disbelief and scorn into one word. “

"—We know it’s not a sports injury. You’ll waste two weeks getting an appointment with a sports doctor, and then he’ll tell you everything is fine. It sounds systemic.”

“—I’ll call Hahn,” he says.

“Good idea.” As usual, Dan is right. I’ve jumped a step; better to see our family doctor first, someone who knows him and can look at the whole picture.

Dr. Hahn fits Dan in the next day, Wednesday, May 8th, and I’m glad. “Tell him I think your speech is getting slurred.”

Dan gives me a look that says he will tell Hahn no such thing.

I have an appointment that day with the optometrist in the building next door to Dr. Hahn’s office, and when I come out, Dan lopes over with our two basenjis, Cooper and Lulu. He takes the dogs—small, shorthaired hounds that don’t bark—along for the ride whenever he can. His gait makes me uneasy; I’m used to his striding, not loping.

“He doesn’t know what’s wrong with me,” says Dan, and we both laugh. Dr. Hahn often confesses puzzlement over our ailments. He’s declared Dan basically fit and told him to keep running. He ordered some blood work through the lab in his building and left for a week’s vacation.

Copyright © Debby Mayer

Sisters: A Novel

Sisters is something better than a fine first novel. It is a brave book and a funny one. Mayer is shrewd without being shrewish, astute without being acid, clever without being coy.

—Julia Cameron, Los Angeles Herald Examiner

Sisters is not . . . one of those hopelessly upbeat books . . . it is a realistic, wryly humorous book with a realistic, wryly humorous heroine trying to survive the wreckage of her love life and independence by a child blithely unaware that she is trampling both underfoot.

—T. J. Banks, Hartford (CT) Courant

For all its modern idiom and mores, Sisters has an old-fashioned, and for me irresistible, theme: a true heroine struggling to live up to her best instincts.

—Lynne Sharon Schwartz, Leaving Brooklyn

+ From Sisters

What the lawyer is telling me is that along with the one life insurance policy and one house I have inherited, in addition to two or three sets of china (depending on what my brother wants), two cars (one totaled), nine pairs of skis, one hundred twelve record albums, eighty-five audiotapes, fourteen framed prints, four hundred Christmas tree ornaments, and, I am sure, over a dozen different kinds of cold cereal, there is one girl.

She is an angular girl, given to leaning in geometric patterns not good for her spine; a long little girl, slender in the legs, face, feet, fingers; a blond girl combining in one head a Breck shampoo ad, Fred Astaire, me at the same age, and the Plaza Hotel’s Eloise. That is, from the nose up, she’s our father and me—high forehead, big eyes, thick eyebrows made of long, coarse hairs. But she has her mother’s discreet nose and family mouth, which is thin, a little tremulous, a wavy line with barely enough lower lip to pout.

Last month Matthew and I saw Swing Time again. “Stephanie reminds me of Fred Astaire,” I said afterward. Matthew studied her school photo, which hangs on the corkboard in my kitchen. “The high forehead,” he said.

“Yeah, and the way they both use their faces so much, like squinting at you when you confuse them, twisting their mouths around and saying, ‘Huh?’”

Last night Matthew and I put the foam rubber pad down on my studio floor and warmed some oil with a few drops of lemon. We massaged each other, first him, then me, smelling tart and loving the oil, oil that makes skin better than velvet or fur . . .

Afterward we stood at the kitchen window, eating sherbet from the container. Outside it was silent, snowing in thick fat flakes; a beautiful storm, not a dangerous one. Below us walked a man in a ski parka led by a large cat on a leash. The cat browsed along a fence, sniffing, poking its head between the iron slats. It had not the usual sleek cat tail but a bushy one with hairs sticking out like a bottle brush, catching the fat snowflakes, speckled with them. Man and cat passed under the streetlight in a gust of wind and disappeared.

We got into bed and talked about Canada—what we might see, how far to take the train. It has become a small treasure, this trip, something we carry with us and take out in spare moments to admire. We went to sleep at three without setting the alarm. And today I am the mother of an eight-year-old-girl.

Copyright © Debby Mayer

Awarded the Jerome Lowell DeJur Award from City College of the City University of New York

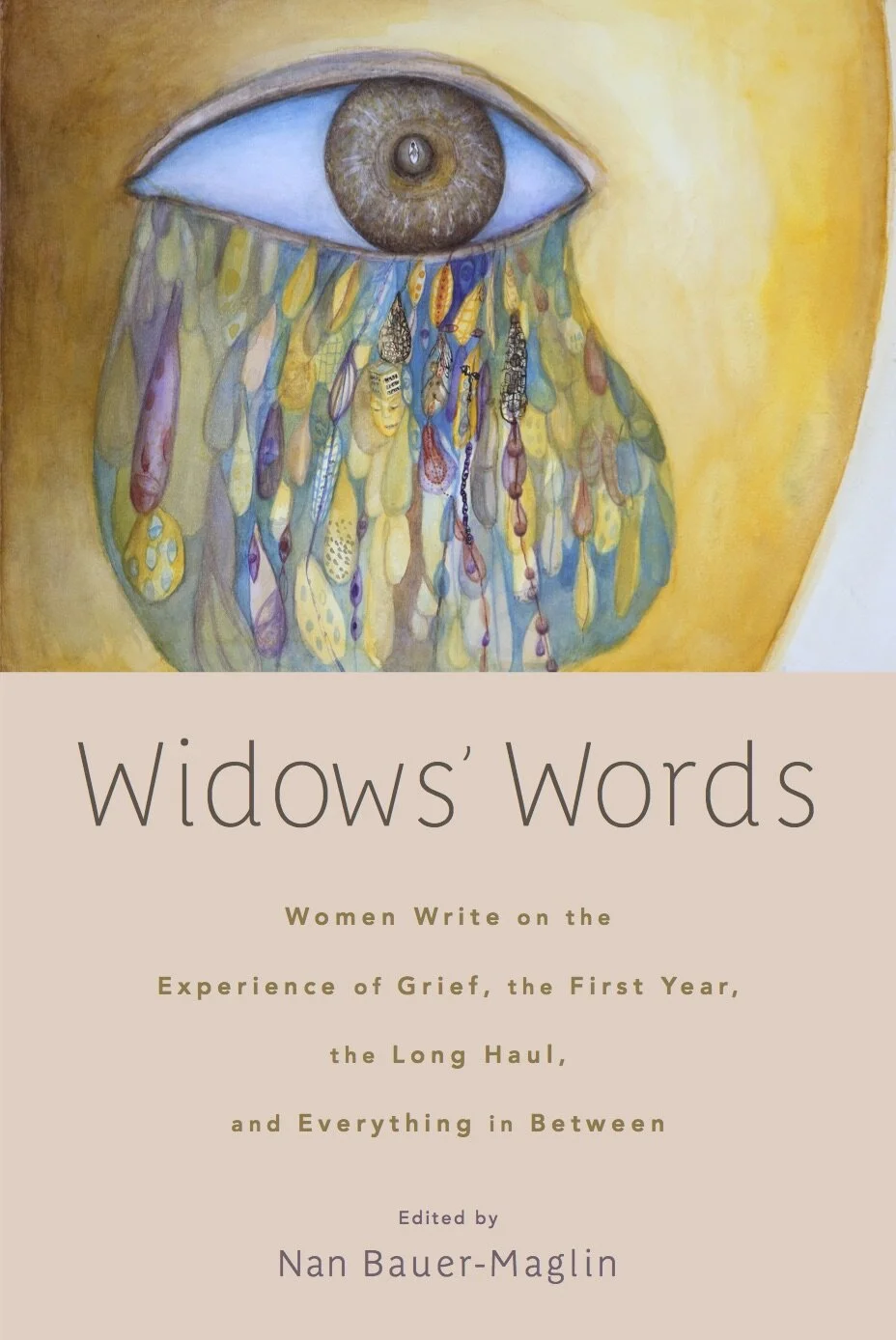

Widows' Words: An Anthology

Widows’ Words is an invaluable tool for understanding loss, mourning and grief, and an equally fascinating and compelling read with diverse and varied points of view, which proved to me that every loss is unique yet universal. [Editor] Nan Bauer-Maglin has brought together many strong female voices that both define and redefine the concept of ‘widow.’

-Jonathan Santloffer, The Widower’s Notebook: A Memoir

“10 Scary Things I Have Done Since My Husband Died” is part of “Long-Time Widows” in Widows’ Words. Here women describe finding new ways to define themselves and to construct a life on their own after the death of a partner.

+ From Widows' Words

From “10 Scary Things I Have Done Since My Husband Died”

Why scary?

Why scary things, asked a friend. Be more positive, she said. These are brave things you’ve done, courageous things.

Because “10 Brave Things” would put half my readers to sleep and send the rest looking for the remote. Courageous is overwrought and overlong.

Still, why scary?

Here’s why:

Spring . . . Dan had died the previous August, after our 25 years together; we were both 56. Now I went downstairs to our small, dark, dirt-floor basement to do a load of laundry and discovered there a good-sized mouse dead on his side next to the dryer.

The laundry and I went right back upstairs. I walked in circles around the deck, knowing that I must rid the basement of that mouse.

I needed to bring a trowel—No! A shovel!—down to the basement to scoop up the mouse, hoping that its remains would not have seeped into the floor (eeuuww).

Or a bag (ugh) or a cloth (Touch it? No way!), as the shovel would be hard to maneuver out the wooden door, tight corner, narrow steps—what if the carcass slid off the shovel and I had to pick it up again, or, worse, what if the carcass slid off the shovel toward me?

I could not stand this.

The mouse could not remain on its side next to the dryer.

I got the shovel. It was big; we didn’t have any small shovels. I made myself take the shovel down the steps.

I couldn’t do it.

I went back up the stairs and stood on the deck in the tentative spring sun, discouraged because I was so squeamish.

Then I did what I had to do.

I went indoors to the kitchen phone and called for help. I called Chris, a young friend who seemed sturdy and brave. With apologies I described the situation, physical (mouse) and mental (me).

“Sure,” she said, “I’ll be right over.”

“Right over” in our rural area meant a 15-minute drive, so I waited patiently on the deck.

Chris showed up on schedule. “Down here?” she said on the deck, outside of the basement.

“Here’s a shovel, or a trowel, and a bag.”

“That’s OK.” Chris waved them away and headed down the steps to the basement, where she had never been before. I figured she would assess the situation and tell me what she needed.

But moments later she returned, holding the mouse by its tail in her bare hand.

“Chris! Not in your bare hand!”

“It’s fine. I’ll just throw it over here into the woods, right?”

I made wash her hands. I thanked her profusely.

“No problem,” she said. “I’m trying to do one scary thing every day.”

I’m trying to do one scary thing every day.

Never had I attempted to be so brave, so courageous.

In my admiration for that goal, for her tackling scary things, from the infinitesimal (my mouse) to the immense (whatever challenged her), this essay is titled in honor of Chris.

Copyright © Debby Mayer

The Secretary: A Short Story

Chris Briggs, courtesy of Upsplash“The Secretary” was published in The New Yorker and awarded a grant in Fiction from the New York Foundation for the Arts.

+ From "The Secretary"

The secretary enters the express elevator. Four men already stand there in a half circle. Each wears a suit in a different shade of gray. They have been chatting, but as soon as the secretary enters and turns to face front they fall silent. The doors close, the elevator starts to rise, and the men begin to jingle the change in their pockets. Nothing then for twelve flights but the elevator, with its mechanical purr, and the sound of the coins, growing more fierce. The secretary pictures quarters and dimes sliding down black crevices, pennies abandoned on bureaus cut from mahogany and oak.

She keeps her back to the men, her eyes low, her mouth still. She is ready to run. A Gypsy may follow her, rattling a tambourine. A witch doctor may jump out from the bush, growling behind a mask, circling her slowly. They call to her now in the elevator, sing to her with the jingle of the change like crimson-tufted birds that never see the sky above the rain forest. We have black magic in our pockets, they say, lightning in our hands.

When the secretary was a little girl, her mother’s friends said to her, “Your hair won’t stay blond like that forever! It’ll go dark as your eyebrows, you’ll see.” Today the secretary has thick strawberry-blond hair and eyebrows such as a student working in charcoal might draw. She has become a secretary as an emergency measure, and has had to put into service clothes she formerly saved for best—a silk dress of cobalt blue, tuxedo pants, a gray suit previously worn only to funerals. A messenger who joins her on the express elevator one morning grins—hey baby, you all right. She smiles back her thanks. Most days, she would rather be a messenger in red high-tops and a black T-shirt, earphones loose around her neck, a bicycle wheel balanced under her fingertips. Messengers, she has noticed, have a lot more style than they did when she was last a secretary, over ten years ago. Her new job pays fairly well, for work that is mildly interesting and very easy. Still, she longs sometimes to drive a little white truck around the city, delivering packages, or even to be her office manager’s assistant, rushing to Wall Street with papers, and wearing jeans to work.

But the secretary is waiting for her ship to come in, and in the meantime, she makes more money than an office boy or a bicycle messenger, and if her ship doesn’t come in she may be able to disguise this stint on her resume. The secretary tries to have fantasies that are practical.

Copyright © Debby Mayer

Edcelina Baby: A Short Story

Gunnar Ridderstrom, courtesy of Upsplash“Edcelina Baby Come Back Home” was published in Redbook, reprinted in Redbook’s Famous Fiction and earned an Honorable Mention in Best American Short Stories.

+ From "Edcelina Baby"

EDCELINA. EDCELINA BABY COME BACK HOME. On the walls here and there in the neighborhood. The A&P on Third Avenue, white chalk on rose brick. Farther up, on a blue tenement, all capitals cry out: EDCELINA MOMMA COME BACK TO ME NOW. Square, neat letters—make no mistake, the voice behind them wants Edcelina to return.

Brian arrived too soon. Ingrid had taken the bus out to LaGuardia extra early so she’d be sure to see the plane come in, see him walk out of it and over to her—

"Miss Ingrid?”

“You’re here!”

“Scare you?” He kissed her mouth lightly. “They changed me to an early flight.”

She stood still, taking in his large, lean frame, face still tanned from tennis, his dark-blond hair.

“Let’s not hang around here!” he said. “We’ll get a cab, right?”

“There’s a bus that’s cheaper—"

“Silly. I get paid expenses.”

So her dream of their sitting together on the bus, watching the city come closer, changed to their sitting in a cab, finding change for the toll. Brian leaned back in the seat, talking. He’d sold a poem about his daughter, plus two others . . . he’d show them to her. He hadn’t been in New York in so long! It was good to be back, He smiled at her, hugged her, kissed her neck.

. . .

“Let’s take a walk!” he said. . . . “Aren’t we near the secondhand bookstores?”

She headed them toward Park Avenue. . . .Near Union Square she saw Mickey’s bicycle chained to a streetlight. It had to be his—he freelanced near here, and nobody else had a twenty-year-old Schwinn. Ingrid looked around and walked a little faster. If Brian hadn’t come, she would have seen Mickey tomorrow night. Maybe all weekend. But if she hadn’t met Brian, she wouldn’t be here. She’d be in an office somewhere, too much in love with Mickey.

“Look! Did you see that?” Brian had her arm.

“No, what?”

“Come on—you’re missing everything!” He put his arm around her then and squeezed every time he wanted her to look at something.

Edcelina is fourteen. Tall for her age, big-breasted, a bit plump—no skinny momma she. Round-faced, with smooth, tan skin; large brown eyes with long, if skimpy lashes; lips full and round that draw up on straight white teeth when she smiles. But smiles are rare for Edcelina—smiles aren’t enough. When something’s funny or pleases her, she laughs, a big “Hah!” and her brown eyes shine.

When she is not with Vicente—or for a while it was Julio—Edcelina is the center of a group of five girls, all shorter or plumper or thinner versions of herself. They walk to school together, notebooks on hips, talking, their heads turned sideways, or laughing, eyes shut, jostling one another. After school maybe a group of boys will play stickball near Edcelina’s building, and after an intense hour of concentrating on the flying balls, they come around to the girls on the stoop. The tallest, handsomest boy of the day talks to Edcelina, looking down at her, his brown hands tossing the ball back and forth, and the other boys talk to her friends.

Copyright © Debby Mayer

Therapy Dogs: A Personal Essay

“Therapy Dogs” was published in the Loss issue of Our Town magazine and awarded a grant in Creative Nonfiction from the New York Foundation for the Arts.

+ From "Therapy Dogs"

Dr. Moore and I are having a family conference. It’s about seven o’clock in the evening; I’ve just arrived at the hospital, and she’s about to depart. She’s given Dan his fourth chemo treatment, second lumbar—an injection into his spine. He’s dozing now, and we stand at the foot of his bed while she tells me things she’s said before—that he’s more attentive this week, and his eye movement continues to improve.

It’s July 10, and Dan’s been in this hospital since May 30. If he isn’t attentive sometimes, I wonder if he’s bored, tired of being asked the same questions every day, but I don’t say that. What I do is take a breath and say: “Would it be all right if I brought our dogs to visit Dan sometimes?”

A nurse gave me this idea, a nurse in training, that is, a robust woman with freckles across her nose, who looked as if she might have grown up on one of the farms still to be found within 30 miles of this hospital. It was early June then, and Dan was on another floor, while neurologists who seemed to consider him a theoretical problem, not a human one, tried to find out what was wrong with him and decide how to treat it. That day, I arrived in the afternoon, to find this pleasant young woman sitting with Dan at the end of the hallway, at the window overlooking the city. He’d had a shower that morning, she reported, and had been very helpful, washing his hair and beard.

Our dogs are basenjis, small, shorthaired African hounds, red with white markings. . . . Cooper, who turned 16 in June, had stopped eating, and that morning I had taken him and Lulu, age 2, to the vet. The vet could find nothing physically wrong with Cooper, beyond his being at least 112 dog-years old.

“She diagnosed depression,” I reported to Dan and the nurse, both of whom listened with grave concern. . . .

When, some days later, the robust nurse-in-training twinkled at us: “I’ve heard that four-legged visitors have been seen on this floor, and others may be welcomed,” my heart leapt, only to be shot down by Marge, the stolid, gray-haired “sit,” planted in her flowered smock in a chair next to Dan’s bed. (A sit is a “safety companion,” Dan’s first sit explained to us. He outweighed Dan by a hundred pounds and kept him from trying to sneak out of bed. “We’re called the sit,” he said, “’cause, we sit.”)

“Not on neurology,” is what Marge said. “Too much dementia.” She saw me sag. “When he gets to oncology,” she said quietly, “ask the doctor.”

Now Dan’s on oncology. It’s been nine weeks since he first had trouble moving on his daily four-mile run. Today he can barely move and he can’t speak. Tomorrow he’ll be 56 years old. I think about Dan’s care every day, and I try to speak for him, so I’m asking our doctor for something I wouldn’t have even mentioned, except that two people in this hospital said a few words to me a month ago that I never forgot.

Dr. Moore is slim, with short, curly hair and large, doll-like blue eyes. “Little Orphan Annie grown up. A runner,” I reported to Dan after my first meeting with her. He nodded, getting the picture. There are people, hospital staff among them, who think Dan doesn’t know what’s going on, but he does.

Tonight Dr. Moore’s eyes are full circles as she thinks. “—I don’t see why not.”

“Oh, thank you! It will make him so happy. Will you please put it in his chart so the nurse on duty will always know.”

She puts it in the chart. She adds that he can leave the floor with family.

“Yeah, we had another patient, doctor let her dogs visit her,” the nurse’s aide with the funny twitch says later that night. “Right before she went into hospice.”

Copyright © Debby Mayer